“There is no better teacher than history in determining the future… There are answers worth billions of dollars in $30 history book.” – Charlie Munger

History doesn’t repeat. It rhymes.

Dec 2022 CPI report came out last week. We saw headline inflation at 6.5% and core inflation at 5.7% (net of energy and food prices). The unemployment rate is the lowest it’s been for decades – with the latest report showing 3.5%. There’s an immense focus on mark to market prices of commodities and securities… analysts chasing the next data point leading to speculative trading days and hours.

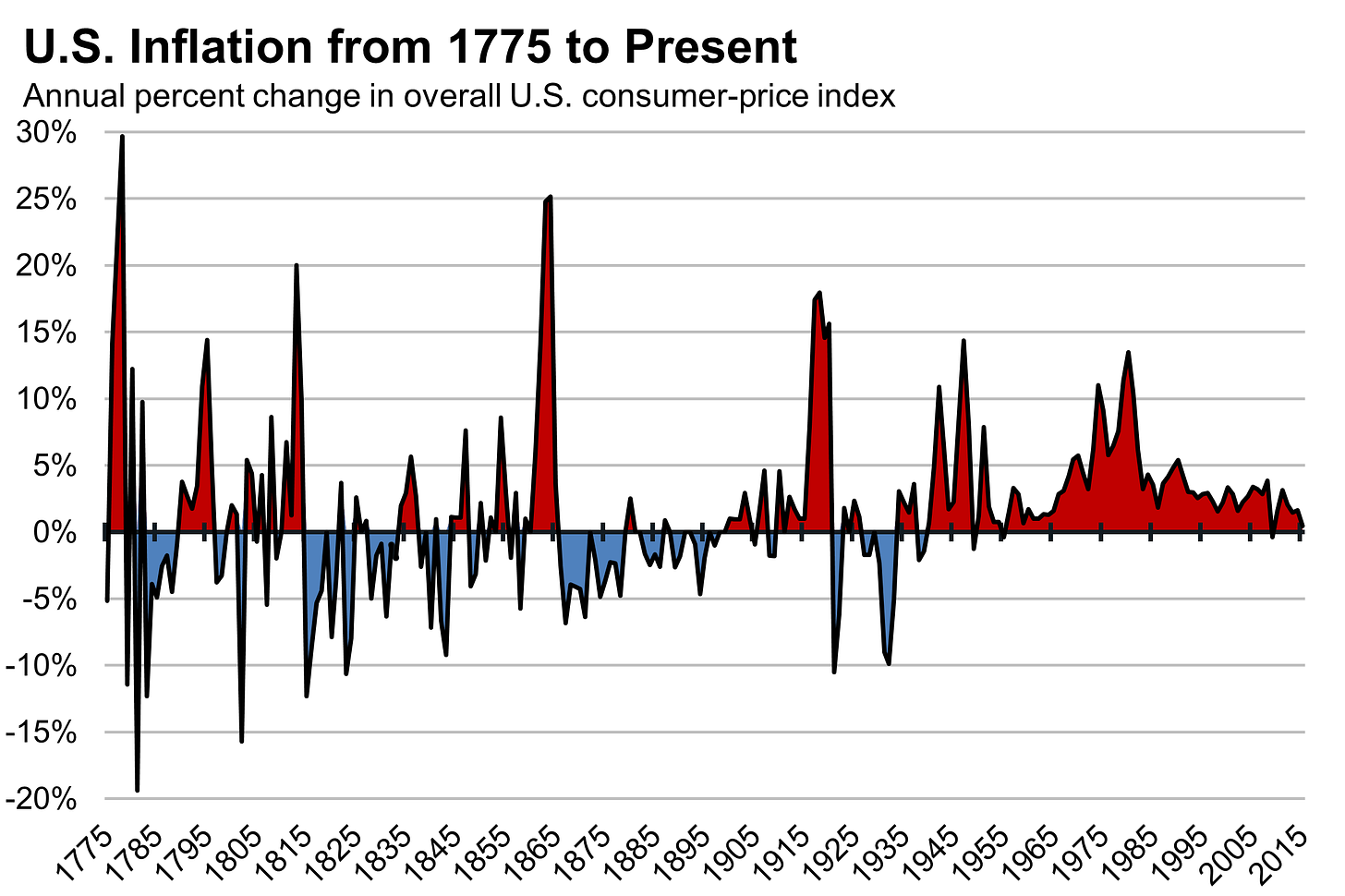

In times like this, I prefer to zoom out to get a grip on what’s to come ahead. This is the first time US is experiencing a real inflationary pressure in 40+ years. Let’s look at the history of inflation.

For our conversation starter, Federal Reserve Bank was established in 1913 and USD become global reserve currency in 1944. If we look at the chart above, we can break it out in three eras.

- Pre-Fed (1775-1913)

- Pre WWII (1913-1945)

- Post WWII (1945-Present)

In pre-Fed era, price stability was challenging as inflation was met with stringent deflation. In pre-WWII era, we experienced WWI, 1918 flu pandemic, and 1929 Great Depression. Some of the most relevant social policies were initiated during this era: 1) Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) in 1932, 2) Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) in 1933, 3) Federal Housing Act (FHA) in 1934, 4) Social Security Act was signed in 1935 and many others.

Great Depression recovery laid the foundation for community welfare and American ingenuity.

The most relevant era to understand modern day inflation, however, is the post WWII era – this will help us better understand the path forward.

First, we haven’t really experienced a rapid deflationary cycle in several decades. I wrote about the Phillips Curve two years ago when inflation wasn’t a topic of discussion. The Fed has been focused on maintaining price stability and max employment. The challenge with max employment is that it’s inflationary by nature.

Second, we have the tools to combat inflation. But combating inflation is a painful and turbulent process. Capital markets know how to price in good news and bad news. It, however, hates uncertainty. And combating inflation is an uncertain process; especially when Fed’s commentary has been “data dependent.”

Third, we can look at the period of The Great Inflation 1964-1982. Paul Volcker, who was chair of the Fed from 1979-1987, grappled with steepest inflationary period in the 20th century. He used the same tools we’re using today: interest rates.

History is fun… let’s talk future, though.

I often use an analogy to discuss how Fed will fight inflation with interest rates as the primary tool.

Think of inflation as a deadly mosquito flying around in your kitchen. Think of interest rates as the hammer – this is the only tool you have to kill the mosquito.

What happens?

You’ll keep swinging. You’ll crack your countertops, you’ll punch a few holes in the wall, you’ll break your appliances… but eventually you’ll kill the mosquito.

It’s a painful process, so why do it? Here’s why: we can always remodel our kitchen and buy new appliances, but we simply can’t afford to be bit by the mosquito. Because it’s deadly and more costly.

Inflation is that mosquito. We simply can’t let it become entrenched in our system. The cost of combating long-term inflationary cycle (as we’ve learned from history) is very hard.

Fed’s credibility is on the line. Fed has the tools to recover a recession (pause rate hikes or even cut rates). The best visual I can come up with is Archimedes lever. Archimedes once said “give me a firm place to stand and a lever and I can move the Earth.” The lever is a force multiplier. Interest rates are a lever to manage growth cycles (cut rates, low cost of capital) and growth contraction (increase rates).

Real interest rates are still negative (core inflation vs fed funds rate). We will need to see positive real rates for a sustained period of time to see inflation cool. This will have a short term impact on unemployment and long term impact on asset prices.