We’re living in the most aggressive monetary and fiscal policy era of all time.

If you’re unfamiliar, here’s a 30 second overview of monetary vs fiscal policy.

Monetary policy is controlled by the Federal Reserve (The Fed). Fiscal policy is managed by the US government.

The Fed is independent of the US Government. The decisions made by the Fed do not have to be approved by any legislative form of the government.

The Fed controls the money supply (they can print money), manage inflation, set interest rates, influence unemployment and more. These are all tools within their toolbox to control monetary policy.

The government focuses on spending the budget and generating revenue (taxation).

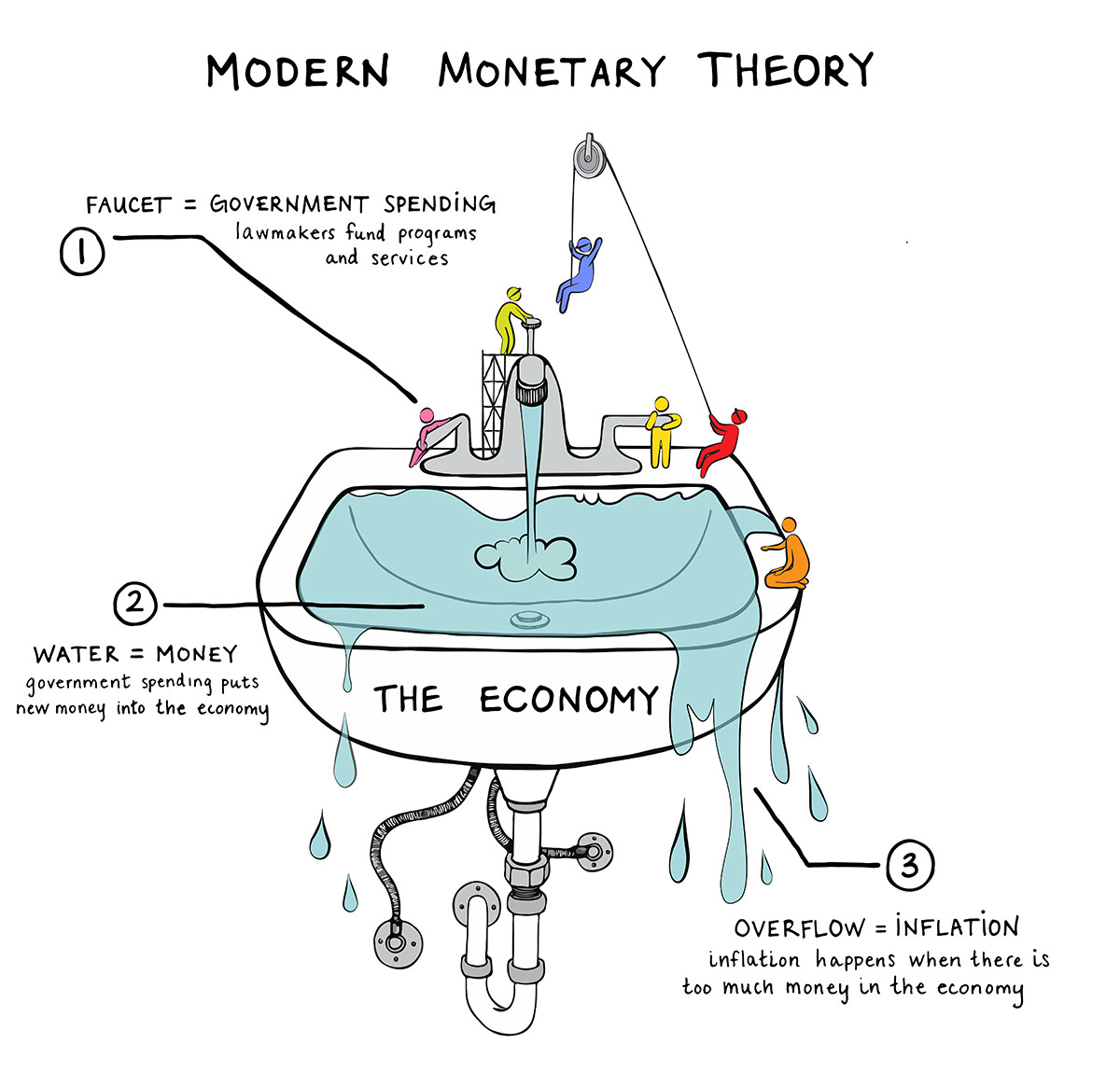

Which leads us to an important concept in economics called Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). This concept is not mainstream yet, but it’s gaining traction.

Illustration: Rose Conlon/Marketplace

MMT enables governments to spend as much as they want without being functionally constrained by their revenue sources. In other words, the US government can spend and take on as much debt as they want because they’re not relying on taxation as a source of revenue.

MMT has come to the fold post The Great Recession in 2008. Supporters of MMT argue that recovery was sluggish, wealth and income inequality has widened and that existing monetary policies haven’t influenced real economic growth. Capital markets have thrived, but real economy hasn’t seen the same increase.

Like all economic theories, MMT has pros and cons.

Proponents of MMT feel that the government can ensure that the highest number of people are employed at all times, there needs to be a universal basic income (UBI), investing in better social programs, building a better infrastructure, and so on.

Theoretically, these are all fair points. But like all ideas, there are challenges and opportunity costs.

First, the government knows how to spend money, but is often bad at allocating capital. It can be inefficient, lethargic in it’s delivery, optimize for equity vs equality, and so on. Spending money is an addiction, a relentless cycle that if not monitored carefully, can get out of control quickly. Political incentives aren’t aligned with public good when this happens; the political party in-charge for a certain period is motivated to spend as much as possible because it can help with re-election. Creating a spending contest between political parties is a recipe for economic calamity.

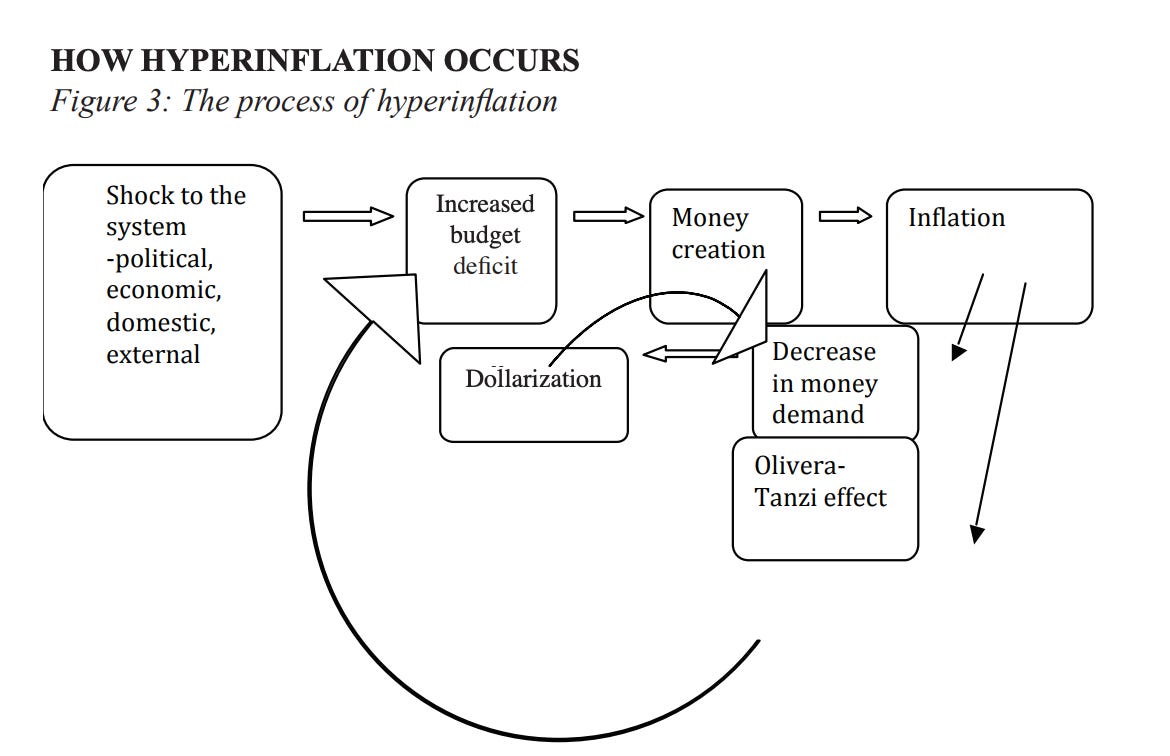

Second, managing inflation is difficult for governments. Central Banks use interest rates to control inflation. In the case of MMT, governments will aim to use taxes to control inflation. Prime example is COVID-19. The US Government, for example, passed several stimulus bills to neutralize the impact. The central bank engaged in quantitative easing (QE) and padded their balance sheets. Leaning on the government to manage inflation is a cause of concern… And can trigger symptoms of hyperinflation.

The phenomenon of hyperinflation is always triggered by an external shock – in our case, COVID-19. If you’re curious about an extreme example, studying Zimbabwe’s hyperinflation problem is fascinating. Here’s a good paper on the economic decline of Zimbabwe.

Lastly, MMT pushes for progressive-extreme legislature which can lead to political instability. Balancing a budget, being fiscally responsible, investing in social welfare efficiently and creating an appropriate taxation legislation are signs of a well-functioning government.

We’re seeing components of MMT in-motion; albeit no form of government has technically declared that they’re following MMT (yet). How governments that have sovereign control – think USA, Japan, UK – over their own currency pursue MMT will be fascinating to observe in the coming years.