In 1936, John Maynard Keynes, wrote “The General Theory of The Economy” where he discusses that key variables to a growing economy are consumption and investments, and that saving money contracts the economy. The argument is simple from his end: when you save more money, you buy less things. When you buy less things, businesses don’t hire as many people, which depresses tax revenue and can impact government spending. When everyone is trying to save, everyone becomes worse off. Keynes didn’t look at savings as an independent variable; rather a by-product of what you didn’t consume. 84 years ago, this concept was rejected by many renowned economists and academics. Today, this theory is accepted and is often used to influence monetary and fiscal policy.

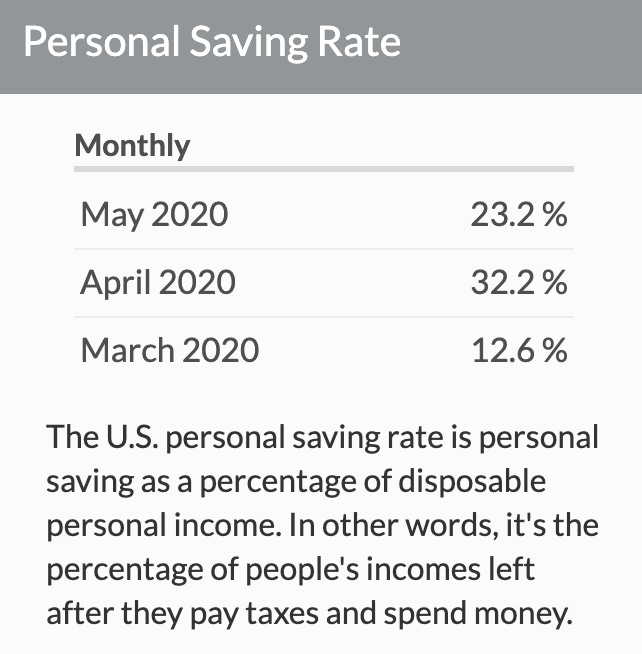

A few weeks back, I wrote about understanding the stock market in the midst of COVID and discussed the GDP equation and a spike in savings in when there’s uncertainty. In May 2020, the personal savings rate was 23% compared to 32% in April. Here’s a quick snapshot of personal savings from the last three months. Data is from BEA.

So, why is this important and how does this relate to COVID? When there’s a pandemic, people immediately react and set up a defense mechanism by saving more. Because 70% of US GDP is dependent on consumption, and 18% on business investments, the precautionary measure of saving more can have a tangible impact on recovery and ripple effects might be felt for years.

COVID has hit retail and service industries the hardest. The Kansas City Fed President, Esther George, recently wrote a paper, where she discusses The Coronavirus Shock: Implications For The Economy and Monetary Policy. If you have interest in macroeconomic policy, then I’d suggest skimming this letter. She discusses labor market developments; how COVID has hit minorities and women employment the hardest. Unemployment levels in the retail and services sector won’t return to normal until there’s a vaccine.

We can’t fully recover until the labor market recovers.

The Fed is always wrestling with inflation and unemployment tradeoffs. Back in 1997, Gregory Mankiew, Professor of Economics at Harvard, wrote about Alan Greenspan’s tradeoff. In 1997, the US was enjoying low inflation and low unemployment. Today, the US is experiencing low inflation coupled with extremely high unemployment. We should expect intense monetary and fiscal policy measures until the end of 2020. Otherwise, personal savings rate will continue to trend between 25-40% which can have long term implications on businesses investments and consumption behaviors, dragging overall GDP for several quarters to come.